There's a wonderful comic from VectorBelly that's been circulating among my Facebook friends in the run-up to the Superbowl:

I'm not a US-rules football fan, but I do enjoy baseball and follow European road bicycle racing avidly. Trying to talk to friends about bike racing, I often get a look that makes me think I must sound like this comic to them. Being a male growing up in the United States, I have been inculcated with US football terminology, even sometimes against my will, so I understand what is discussed in an interview, but VectorBelly illustrates perfectly my apathy about it.

It's not that I dislike the sport of US-rules football. Yes, it's violent. Yes, professional players lead off-field lives of otherworldly wealth and extravagance that seem to necessitate values that are entirely antithetical to the foundations of sportsmanship. Yes, it promulgates gender stereotypes, something I'm increasingly sensitive to as I come to appreciate how much of my life-long experience of not-belonging can be traced to my inability (and disinterest) to fit into conventional expressions of masculinity. All that said, none of this is unique to football -- and, indeed, my own beloved sport of cycling is shot through with its own moral failings -- but I nonetheless frequently find myself actively disparaging US-rules football generally and Superbowl Sunday in particular.

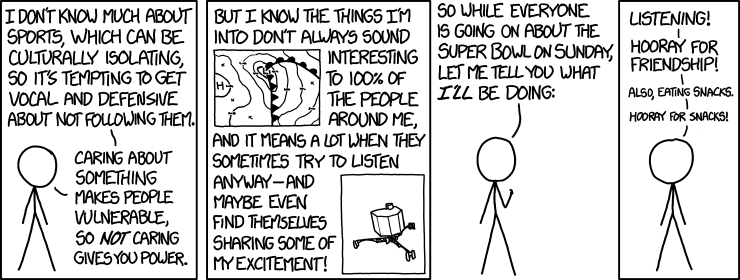

Randall Munroe posted a very different commentary on today's festivities that got me thinking about why I do this:

My first reaction to this was, "Yes! Exactly! This helps me reconcile my ambivalence about football with my desire to participate with friends' appreciation for it." How often I've wished to have a friend who loves cycling (or planetary science or electronic music) as much as I do -- and how wildly I've enthused when I find someone who does! This revealed a bridge.

Last week, a new friend from work invited me over to his house to watch the Superbowl. We've had a great deal of trouble coordinating our schedules to get together (for months now), so the game seemed like a perfect opportunity, lubricated by my newfound insight from Mr. Munroe. But the more I thought about it, the more I dreaded sitting and watching the game with him: it felt like I was poisoning the young relationship, as I anticipated pretending not to hate every minute of the game while trying to enjoy his company. I heard myself think it: "hate every minute of the game." Wow. I realized that I didn't really appreciate the depth of my antipathy.

So I started looking more closely to see what was bugging me. Reversing the thought experiment, I imagined myself attending a live

game with this friend, in a stadium, and I could see myself actually

enjoying the

experience (chilly though it might be). But, as I pictured myself watching the Superbowl on the TV in the comfort of my friend's living room, I felt waves of revulsion. I realized it's not the game, not the athletes, not the gender stereotypes, none of that: it was the unrestrained, unabashed, even celebrated commercialism.

This is what I react to, that I find so deeply repellant; it feels like an utter surrender of our collective intellect to the vast and growing powers of our media. And it's not limited to the game; during the weeks and months before the Superbowl, the most powerful corporations vie for seconds-long spots in front of its audience. They wave red capes of teasers -- ads for ads -- before the eagerly anticipating throngs; commentators on the ads offer critiques on their quality, cost, and effectiveness; office, bar, even dinner-table discussions center around which ads are best and which commentators got it wrong. Entertainment corporations vie for the right to present their performers during half-time, performers whose careers are ads for themselves, and another population of commentators weighs in on the process, and more office, bar, and dinner talks are given over to media content. By the time the actual Superbowl comes around, there's as much or more anticipation of the propaganda events as the sporting outcomes. The propaganda for the propaganda for the game has become the main event, and the game has become a field on which the sport of media is played.

Watching the Superbowl, I am excruciatingly reminded of our elections: our leaders

have become fodder for the entertainment machine in the same way that sports

have. The metaphor of the horserace is no longer as useful for our democratic process as the

pre-Superbowl ad campaign: meta-levels of ads and commentary and polls folding in

on themselves to the point that the candidates for office become

superfluous. To this degree, we have ceded our democracy to the

media.

The fact that the navel-gazing echo-chamber of the media industry is masturbating to pictures of itself is neither my deepest concern nor particularly surprising. The most painful aspect of all this for me is the fact of our gleeful participation in it, the handing over of power in the broadest sense. I feel thrown into a scene from Brave New World, with crowds of beautiful minds swept away by tsunamis of mindless distraction, grateful for the relief from choice that the media provides, paying the fare for the ride without thought (by definition) to its cost to themselves. I half expect to see pink clouds of Soma wafting through the Superbowl stadium and falling lovingly from the television speakers. I think to myself, "I'm glad I'm not a Delta."

This, of course, is an unmitigatedly cynical thought. Like all of us in the West, I am a consumer of ads and, even if I tell myself I don't, I'm sure I surrender more of my free will to their sway than I admit. Conversely, not all who consume ads -- not all who enjoy them -- give over the entirety of their intelligence and choice to them. And our degree of choice, of free will, is, I've come to believe, much, much smaller than we generally care to consider, so avoiding its surrender is proportionately difficult. Regardless, I have decided not to resist my antipathy toward the media's coup over US-rules football; my friend and I have rescheduled to another day.

I had the thought to start (or join in on, as it's likely others have thought of it) a hashtag poking fun at the Superbowl: #nationalsportsingday. This morning's cognitive perambulations have led me to a different idea: #nationalcommercialingday. Raise awareness -- but really, not nominally; let's actively be aware here. The media are not evil, or at least they are only as evil as we empower them to be. We don't need to boycott them, but rather merely be mindful of what we consume. Let us choose what we choose because we like it, not simply because it seems to be the only choice. It's not useful for the media to go away, but it is useful for us to mind how much we let them run things. So, let's celebrate our choice on #nationalcommercialingday.

Sunday, February 1, 2015

Sunday, January 25, 2015

Rings True

This piece has been a long time coming: the create date on the file folder goes back to September of 2013. That month was an especially challenging time of my life and things didn't let up for more than year after that. It's not an accident, then, that this piece is fairly tumultuous and noisy -- even painful at moments. That said, it is ultimately about the process of finding one's truth, learning to hear and listen to that voice that is most personally meaningful, which has also been a theme of my life since I started writing this.

The inspiration for the piece came from Hans Christian Andersen's story of the same name. From my first reading of it years ago, the tale captured for me that sense of seeking something hard to identify and even harder to direct oneself toward and, ultimately, grasp. Andersen of course uses strongly Christian imagery in his story; as an atheist, I have a different relationship to what he sees as a spiritual journey, but the experience he describes, however one interprets it, is one that resonates powerfully with me. I did not directly follow Andersen's allegory here, but rather took his metaphor for the call of the spirit -- The Bell -- and developed it to represent my own experiences with truth seeking.

As it evolved, the piece fell into three sections, the order of which is not meaningful beyond that I felt they worked musically. Of the three, the first section plays the most literally with the idea of seeking something. In short order, it begins to explore the ways in which we find ourselves distracted from our search by pleasant things and by goals and ambitions; as our attention is increasingly focused on these latter, it's easy to lose contact with that which initially called to us. In the second section, I feel around the idea that we sometimes rebel against relatively empty ambitions and seek reconnection with that truth through the rich and compelling beauty of religious and spiritual practices. The aid that these practices provide in locating our truth, however, can be fragile and is often and painfully derailed by the intrusive demands of day-to-day life. The third section explores the challenge of the inner path, how difficult it can be to distinguish the ring of truth from all the other voices -- thoughts and feelings, ideas and sensations -- within us. Throughout the whole piece, though, chimes the bell, even if, as time goes on, it rings more softly and less frequently.

Generically, this is a mix of musique concrete with synthetic and sampled percussion. I love ambient sound and delight in listening to the symphony of the city or the conversations of crows or the peculiar hum of my refrigerator. On the other hand, as I've discussed elsewhere, for me what distinguishes noise from music is the presence of a sense of intention, of direction. Thus, it is my intent -- and hope -- that this work comes across as more than a cacophonous collection of found sounds and actually leads the listener through a sequence of meaningful experiences. Just as it's not an accident that this is a noisy piece, it's also not an accident that it took me nearly a year and a half to complete it; along with being emotionally confronting (for me, at least), it is perhaps the most complex piece I've written. I spent a lot of time locating samples, reordering and layering them, moving them about in aural space, all with the goal of replicating in real sounds my internal sense of the task of finding my truth. In other words, working on the piece was itself an act of authenticity, of distinguishing, listening to, and following my own bell.

Technical notes: This piece was created in Apple's Logic Pro 9 and its native plug-ins; it uses sounds recorded from a Yamaha S-08 synthesizer and lots of real-world samples from Freesound.org and recorded from public broadcast resources. The voice of The Bell was created with Arturia's Moog Modular V.

The inspiration for the piece came from Hans Christian Andersen's story of the same name. From my first reading of it years ago, the tale captured for me that sense of seeking something hard to identify and even harder to direct oneself toward and, ultimately, grasp. Andersen of course uses strongly Christian imagery in his story; as an atheist, I have a different relationship to what he sees as a spiritual journey, but the experience he describes, however one interprets it, is one that resonates powerfully with me. I did not directly follow Andersen's allegory here, but rather took his metaphor for the call of the spirit -- The Bell -- and developed it to represent my own experiences with truth seeking.

As it evolved, the piece fell into three sections, the order of which is not meaningful beyond that I felt they worked musically. Of the three, the first section plays the most literally with the idea of seeking something. In short order, it begins to explore the ways in which we find ourselves distracted from our search by pleasant things and by goals and ambitions; as our attention is increasingly focused on these latter, it's easy to lose contact with that which initially called to us. In the second section, I feel around the idea that we sometimes rebel against relatively empty ambitions and seek reconnection with that truth through the rich and compelling beauty of religious and spiritual practices. The aid that these practices provide in locating our truth, however, can be fragile and is often and painfully derailed by the intrusive demands of day-to-day life. The third section explores the challenge of the inner path, how difficult it can be to distinguish the ring of truth from all the other voices -- thoughts and feelings, ideas and sensations -- within us. Throughout the whole piece, though, chimes the bell, even if, as time goes on, it rings more softly and less frequently.

Generically, this is a mix of musique concrete with synthetic and sampled percussion. I love ambient sound and delight in listening to the symphony of the city or the conversations of crows or the peculiar hum of my refrigerator. On the other hand, as I've discussed elsewhere, for me what distinguishes noise from music is the presence of a sense of intention, of direction. Thus, it is my intent -- and hope -- that this work comes across as more than a cacophonous collection of found sounds and actually leads the listener through a sequence of meaningful experiences. Just as it's not an accident that this is a noisy piece, it's also not an accident that it took me nearly a year and a half to complete it; along with being emotionally confronting (for me, at least), it is perhaps the most complex piece I've written. I spent a lot of time locating samples, reordering and layering them, moving them about in aural space, all with the goal of replicating in real sounds my internal sense of the task of finding my truth. In other words, working on the piece was itself an act of authenticity, of distinguishing, listening to, and following my own bell.

Technical notes: This piece was created in Apple's Logic Pro 9 and its native plug-ins; it uses sounds recorded from a Yamaha S-08 synthesizer and lots of real-world samples from Freesound.org and recorded from public broadcast resources. The voice of The Bell was created with Arturia's Moog Modular V.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)